Landscaping for Lightning Bugs

Fireflies, lightning bugs, whatever you call them, you may have noticed an influx of the glowing evening insects this year. States throughout the Mid-Atlantic are reporting higher quantities of lightning bugs than years past. I, personally, can attest to the silent rave that happens in my yard every evening now, tiny yellow strobes composing a tapestry of starry light throughout the darkness. My childhood, as I’m sure many of yours are, is filled with memories of chasing lightning bugs around the yard, collecting them in my yellow plastic bucket with a red plastic screen top, and shaking them to encourage them to glow (my parents still chuckle about my ignorant brutality to this day).

As the decades have passed and memories of nostalgic, sepia-toned summers have long waned, so, seemingly, have the lightning bug populations. Summer after summer, their numbers appeared to be declining further, until at one point it was exciting to even glimpse just a few small handfuls. Perhaps we’re just lucky this year, and our fiery friends are experiencing a boom. I’d like to think, though, that the semi-recent turn to incorporating more native plants into landscapes paired with the intensive efforts to push legislation banning the use of neonicotinoids has helped to support a flush of flashing insects. After all, lightning bugs need somewhere to rest their wings and regain energy during the daytime to perform their nighttime spectacle.

Just like spindly, awkward mayflies, lightning bugs are harbingers of healthy water sources. Unlike mayflies, which genuinely seem to creep most people out, lightning bugs were born with the benefit of being downright adorable. It certainly helps that they’re capable of emitting their own light, intriguing even the wariest of entomophobes. Lightning bugs span multiple genera, with New Jersey alone being home to 26 unique species – three of which are currently listed as “threatened” on the IUCN species list. Lightning bugs are not actually “bugs”, but soft bodied beetles, comprising several different species that endemic to North America. Each of these firefly species produces a series of chemicals that enables them to glow, although scientists are unsure of how they regulate the on-and-off mechanism that allows them to communicate with one another. Depending on the species, the light emitted from lightning bug abdomens may appear as warm yellows, cool yellow-greens, light greens, light blues, and even muted red tones. Both males and females are capable of producing light, although this is exclusive to fireflies East of the Great Plains – those found West of the Plains typically do not produce light as adults. Of the Eastern and Western species, the larvae of North American lightning bugs are also known to emit a soft light, prompting the term “glow-worms” to describe the predaceous little fellas. Firefly larvae are known to consume soil-dwelling insects such as snails, slugs and other soft-bodied invertebrates, making them beneficial garden companions for controlling unwanted pests.

So, how do we best support all stages of lightning bug life as plant people? Lightning bugs require a biodiverse habitat for coverage and sustenance, with larvae typically living amidst rotted logs and other decaying organic matter, and adults resting on the undersides of tree leaves and camouflaging themselves within tall grasses. It’s not uncommon to find flashing adults on the undersides of leaves in the evening, or even crawling around low-growing groundcovers and grasses, casting beacons of light against the silhouettes of blades and foliage. Providing a mixture of canopy heights is crucial for the success of lightning bug reproductive activities. Female fireflies tend to stay low to the ground, preferring tall grasses for protection while waiting for the right male to wander by.

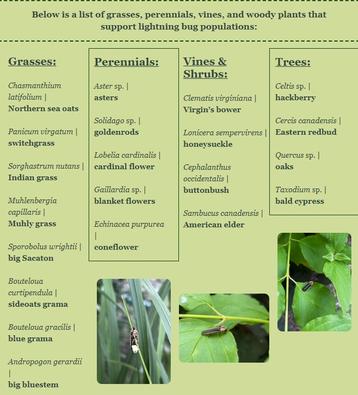

While lightning bugs tend to thrive in riparian zones and lay their eggs around richly organic woodland sites, it’s not uncommon for them to live in a wide range of habitats and rely on a variety of plants for shelter. Attempting to mimic natural firefly habitats, complete with rich, organic soil and perhaps a water feature or two is a surefire way to invite fireflies to the landscape year after year. Below is a list of grasses, perennials, shrubs, vines, and trees that support lightning bug populations:

Grasses:

Chasmanthium latifolium | Northern sea oats

Panicum virgatum | switchgrass

Sorghastrum nutans | Indian grass

Muhlenbergia capillaris | Muhly grass

Sporobolus wrightii | big Sacaton

Bouteloua curtipendula | sideoats grama

Bouteloua gracilis | blue grama

Andropogon gerardii | big bluestem

Perennials:

Aster sp. | asters

Solidago sp. | goldenrods

Lobelia cardinalis | cardinal flower

Gaillardia sp. | blanket flowers

Echinacea purpurea | coneflower

Vines:

Clematis virginiana | Virgin’s bower

Lonicera sempervirens | honeysuckle

Shrubs:

Cephalanthus occidentalis | buttonbush

Sambucus canadensis | American elder

Trees:

Celtis sp. | hackberry

Cercis canadensis | Eastern redbud

Quercus sp. | oaks

Taxodium sp. | bald cypress

Make sure to add these to your next order, or start planning your fall orders now for our future crops, to help support the next generation of lightning bugs!

10 Plants That Attract Fireflies (Plants They Love) - Pond Informer

Plants for Fireflies | List of Native Plants Good for Fireflies | Firefly.org

Where are all the fireflies? A concerning trend threatens lightning bugs. - nj.com

Most Common Names for Fireflies | What is Firefly in Other Foreign Languages? | Firefly.org

Types of Fireflies - Firefly Conservation & Research